Help When Needed: Apply the Research Credit Against Payroll Taxes

Here’s an interesting option if your small company or start-up business is planning to claim the research tax credit. Subject to limits, you can elect to apply all or some of any research tax credits that you earn against your payroll taxes instead of your income tax. This payroll tax election may influence some businesses to undertake or increase their research activities. On the other hand, if you’re engaged in or are planning to engage in research activities without regard to tax consequences, be aware that some tax relief could be in your future.

Here are some answers to questions about the option.

Why is the election important?

Many new businesses, even if they have some cash flow, or even net positive cash flow and/or a book profit, pay no income taxes and won’t for some time. Therefore, there’s no amount against which business credits, including the research credit, can be applied. On the other hand, a wage-paying business, even a new one, has payroll tax liabilities. The payroll tax election is thus an opportunity to get immediate use out of the research credits that a business earns. Because every dollar of credit-eligible expenditure can result in as much as a 10-cent tax credit, that’s a big help in the start-up phase of a business — the time when help is most needed.

Which businesses are eligible?

To qualify for the election a taxpayer:

- Must have gross receipts for the election year of less than $5 million and

- Be no more than five years past the period for which it had no receipts (the start-up period).

In making these determinations, the only gross receipts that an individual taxpayer takes into account are from his or her businesses. An individual’s salary, investment income or other income aren’t taken into account. Also, note that neither an entity nor an individual can make the election for more than six years in a row.

Are there limits on the election?

Research credits for which a taxpayer makes the payroll tax election can be applied only against the employer’s old-age, survivors and disability liability — the OASDI or Social Security portion of FICA taxes. So the election can’t be used to lower 1) the employer’s liability for the Medicare portion of FICA taxes or 2) any FICA taxes that the employer withholds and remits to the government on behalf of employees.

The amount of research credit for which the election can be made can’t annually exceed $250,000. Note too that an individual or C corporation can make the election only for those research credits which, in the absence of an election, would have to be carried forward. In other words, a C corporation can’t make the election for research credits that the taxpayer can use to reduce current or past income tax liabilities.

The above Q&As just cover the basics about the payroll tax election. And, as you may have already experienced, identifying and substantiating expenses eligible for the research credit itself is a complex area. Contact us for more information about the payroll tax election and the research credit.

© 2022

Numbers tell only part of the story. Comprehensive footnote disclosures, which are found at the end of reviewed and audited financial statements, provide valuable insight into a company’s operations. Unfortunately, most people don’t take the time to read footnotes in full, causing them to overlook key details. Here are some examples of hidden risk factors that may be unearthed by reading footnote disclosures.

Related-party transactions

Companies may give preferential treatment to, or receive it from, related parties. Footnotes are supposed to disclose related parties with whom the company conducts business.

For example, say a tool and die shop rents space from the owner’s parents at a below-market rate, saving roughly $120,000 each year. Because the shop doesn’t disclose that this favorable related-party deal exists, the business appears more profitable on the face of its income statement than it really is. If the owner’s parents unexpectedly die — and the owner’s brother, who inherits the real estate, raises the rent to the current market rate — the business could fall on hard times, and the stakeholders could be blindsided by the undisclosed related-party risk.

Accounting changes

Footnotes disclose the nature and justification for a change in accounting principle, as well as that change’s effect on the financial statements. Valid reasons exist to change an accounting method, such as a regulatory mandate. But dishonest managers can use accounting changes in, say, depreciation or inventory reporting methods to manipulate financial results.

Unreported and contingent liabilities

A company’s balance sheet might not reflect all future obligations. Detailed footnotes may reveal, for example, a potentially damaging lawsuit, an IRS inquiry or an environmental claim. Footnotes also spell out the details of loan terms, warranties, contingent liabilities and leases.

Significant events

Outside stakeholders appreciate a forewarning of impending problems, such as the recent loss of a major customer or stricter regulations in effect for the coming year. Footnotes disclose significant events that could materially impact future earnings or impair business value.

Transparency is key

In today’s uncertain marketplace, it’s common for investors, lenders and other stakeholders to ask questions about your disclosures and request supporting documentation to help them make better-informed decisions. We can help you draft clear, concise footnotes and address stakeholder concerns. Contact us for more information.

© 2022

Under some circumstances, an employer that sponsors a 401(k) might wish to amend its plan to exclude part-time employees and offer the benefit only to full-time staff members. Is such an approach allowed under the rules for qualified plans?

Coverage and service rules

Employers have considerable freedom to decide which categories of employees can participate in their 401(k) plans. However, this freedom isn’t unlimited.

For example, eligibility restrictions must avoid violating the minimum coverage rules. And service-based exclusions cannot violate the minimum service rules.

Under those rules, employees generally can’t be required to have more than 1,000 hours of service in a designated 12-month period before being eligible to participate in a 401(k) plan. In addition, long-term part-time employees can’t be required to have more than three consecutive 12-month periods of at least 500 hours of service before they can make elective deferrals.

Note: Deferrals aren’t required under the three-year rule before 2024, however, because only 12-month periods after 2020 must be counted.

Tricky thresholds

So, let’s say you’d like to exclude all part-time employees regardless of their actual service. This sort of categorical exclusion might seem different from an hours-of-service requirement, but part-time status is typically based on anticipated or scheduled service. And, in the IRS’s view, a service-based eligibility threshold that doesn’t count actual hours of service will fail the hour-counting rules if, in operation, it excludes employees whose actual service satisfies an applicable hour-counting threshold.

For instance, if your plan were to define part-timers as employees who are “regularly scheduled” to work 20 or fewer hours a week, the plan might end up excluding employees who work 20 hours a week for 52 weeks and, therefore, have 1,040 hours of service for the year.

In that event, your plan would be using a service-based threshold to exclude employees who, in fact, have satisfied the 1,000-hour minimum service rule. Beginning in 2024, employees with even fewer hours won’t be excludable from elective deferrals on account of their service if they work at least 500 hours in three consecutive 12-month periods.

A potential solution

One potential approach to excluding employees who aren’t full-timers is to look for a common, non–service-based denominator among them that you wish to exclude, such as job function or job location.

For example, let’s say most of your part-time employees are performing the same job function or work at the same location, and you’re willing to exclude all other employees who perform the same job function or work at the same location. In this case, you might be able to craft a plan eligibility rule that excludes those part-timers without violating the minimum service rules.

Be careful, though, because at least one IRS representative has indicated that even criteria that aren’t service-based could violate the rules if they merely disguise an improper plan eligibility rule.

Clear language

Finally, bear in mind that errors in applying the 401(k) plan eligibility rules to part-time employees frequently turn up in voluntary compliance and IRS audits. It’s critical that your plan’s terms clearly state your design choices — especially when excluding certain classes of employees. Moreover, you should routinely review plan language to ensure it reflects changing employment practices. Contact us for more information.

© 2022

For many business owners, estate planning and succession planning go hand in hand. As the owner of a closely held business, you likely have a significant portion of your wealth tied up in the business. If you don’t take the proper estate planning steps to ensure that the business lives on after you’re gone, you may be placing your family at risk.

Separate ownership and management succession

One reason transferring a family business can be a challenge is the distinction between ownership and management succession. When a business is sold to a third party, ownership and management succession typically happen simultaneously. But in the context of a family business, there may be reasons to separate the two.

From an estate planning perspective, transferring assets to the younger generation as early as possible allows you to remove future appreciation from your estate, minimizing any estate taxes due after your death. On the other hand, you may not be ready to hand over the reins or you may feel that your children aren’t ready to take over.

There are strategies family business owners can use to transfer ownership without immediately giving up control, including:

- Transferring ownership to the next generation in the form of nonvoting stock,

- Placing business interests in a trust, family limited partnership or other vehicle that allows the owner to transfer substantial ownership interests to the younger generation while retaining management control, or

- Establishing an employee stock ownership plan.

Another reason to separate ownership and management succession is to deal with family members who aren’t involved in the business. Providing heirs outside the business with nonvoting stock or other equity interests that don’t confer control can be an effective way to share the wealth while allowing those who work in the business to take over management.

Work around conflicts

Another unique challenge presented by a family business is that the older and younger generations may have conflicting financial needs. Fortunately, there are strategies available to generate cash flow for the owner while minimizing the burden on the next generation.

For example, you may want to structure an installment sale of the business to your heirs. This option can provide you liquidity while easing the burden on your adult children or other heirs. It may also improve the chances that the purchase can be funded by cash flows from the business. Plus, as long as the price and terms are comparable to arm’s-length transactions between unrelated parties, the sale shouldn’t trigger gift or estate tax.

Get an early start

Regardless of your strategy, the earlier you start planning the better. Transitioning the business gradually over several years or even a decade or more gives you time to educate family members about your succession planning philosophy. It also allows you to relinquish control over time, and to implement tax-efficient business structures and transfer strategies. Because each family business is different, work with us to identify appropriate strategies in line with your objectives and resources.

© 2022

Businesses with multiple owners generally benefit from a variety of viewpoints, diverse experience and strategic areas of specialization. However, there’s a major risk: the company can be thrown into tumult if one of the owners decides, or is compelled by circumstances, to leave.

A logical and usually effective solution is to create and implement a buy-sell agreement. This is a legal document that spells out how an owner’s share in the business will be valued and transferred following a “triggering event” such as voluntary departure, divorce, disability or death.

Buy-sell benefits

A well-designed “buy-sell” (as it’s often called for short) manages risk in various ways. For starters, it helps keep ownership of the business within the family or another select group — for example, people actively involved in the enterprise rather than outsiders. In the case of a divorce, an agreement can prevent an owner’s soon-to-be former spouse from acquiring a business interest.

The death of an owner is a particularly difficult and often complex situation. A buy-sell can establish the value of the business for gift and estate tax purposes so long as certain requirements are met. The agreement is then able to play a role in providing the owner’s family with liquidity to pay estate taxes and other expenses.

Tax impact

Generally, buy-sell agreements are structured as either:

- Cross-purchase, under which the remaining owners buy the departing owner’s shares, or

- Redemption, under which the business entity itself buys the departing owner’s shares.

From a tax perspective, cross-purchase agreements are generally preferable. The remaining owners receive the equivalent of a “stepped-up basis” in the purchased shares. That is, their basis for those shares will be determined by the price paid, which is the current fair market value.

Having this higher basis will reduce their capital gains if they sell their interests down the road. Also, if the remaining owners fund the purchase with life insurance, the insurance proceeds are generally tax-free.

Redemption agreements, on the other hand, can trigger a variety of unwanted tax consequences. These include corporate alternative minimum tax, accumulated earnings tax or treatment of the purchase price as a taxable dividend.

However, there’s a disadvantage to cross-purchase agreements. That is, the owners, rather than the company, are personally responsible for funding the purchase of a departing owner’s interest. And if they use life insurance as a funding source, each owner will need to maintain policies on the life of each of the other shareholders — a potentially cumbersome and expensive arrangement.

Worth the effort

As you can see, the tax and legal details of a buy-sell agreement can get quite technical. But don’t let that discourage you from establishing one or occasionally reviewing a buy-sell you already have in place. We can help you in either case.

© 2022

The next quarterly estimated tax payment deadline is June 15 for individuals and businesses so it’s a good time to review the rules for computing corporate federal estimated payments. You want your business to pay the minimum amount of estimated taxes without triggering the penalty for underpayment of estimated tax.

Four methods

The required installment of estimated tax that a corporation must pay to avoid a penalty is the lowest amount determined under each of the following four methods:

- Under the current year method, a corporation can avoid the estimated tax underpayment penalty by paying 25% of the tax shown on the current tax year’s return (or, if no return is filed, 25% of the tax for the current year) by each of four installment due dates. The due dates are generally April 15, June 15, September 15 and January 15 of the following year.

- Under the preceding year method, a corporation can avoid the estimated tax underpayment penalty by paying 25% of the tax shown on the return for the preceding tax year by each of four installment due dates. (Note, however, that for 2022, certain corporations can only use the preceding year method to determine their first required installment payment. This restriction is placed on a corporation with taxable income of $1 million or more in any of the last three tax years.) In addition, this method isn’t available to corporations with a tax return that was for less than 12 months or a corporation that didn’t file a preceding tax year return that showed some tax liability.

- Under the annualized income method, a corporation can avoid the estimated tax underpayment penalty if it pays its “annualized tax” in quarterly installments. The annualized tax is computed on the basis of the corporation’s taxable income for the months in the tax year ending before the due date of the installment and assuming income will be received at the same rate over the full year.

- Under the seasonal income method, corporations with recurring seasonal patterns of taxable income can annualize income by assuming income earned in the current year is earned in the same pattern as in preceding years. There’s a somewhat complicated mathematical test that corporations must pass in order to establish that their income is earned seasonally and that they therefore qualify to use this method. If you think your corporation might qualify for this method, don’t hesitate to ask for our assistance in determining if it does.

Also, note that a corporation can switch among the four methods during a given tax year.

We can examine whether your corporation’s estimated tax bill can be reduced. Contact us if you’d like to discuss this matter further.

© 2022

The downturn in the stock market may have caused the value of your retirement account to decrease. But if you have a traditional IRA, this decline may provide a valuable opportunity: It may allow you to convert your traditional IRA to a Roth IRA at a lower tax cost.

Traditional vs. Roth

Here’s what makes a traditional IRA different from a Roth IRA:

Traditional IRA. Contributions to a traditional IRA may be deductible, depending on your modified adjusted gross income (MAGI) and whether you (or your spouse) participate in a qualified retirement plan, such as a 401(k). Funds in the account can grow tax deferred.

On the downside, you generally must pay income tax on withdrawals. In addition, you’ll face a penalty if you withdraw funds before age 59½ — unless you qualify for a handful of exceptions — and you’ll face an even larger penalty if you don’t take your required minimum distributions (RMDs) after age 72.

Roth IRA. Roth IRA contributions are never deductible. But withdrawals — including earnings — are tax free as long as you’re age 59½ or older and the account has been open at least five years. In addition, you’re allowed to withdraw contributions at any time tax- and penalty-free. You also don’t have to begin taking RMDs after you reach age 72.

However, the ability to contribute to a Roth IRA is subject to limits based on your MAGI. Fortunately, no matter how high your income, you’re eligible to convert a traditional IRA to a Roth. The catch? You’ll have to pay income tax on the amount converted.

Your tax hit may be reduced

This is where the “benefit” of a stock market downturn comes in. If your traditional IRA has lost value, converting to a Roth now rather than later will minimize your tax hit. Plus, you’ll avoid tax on future appreciation when the market goes back up.

It’s important to think through the details before you convert. Here are some of the issues to consider when deciding whether to make a conversion:

Having enough money to pay the tax bill. If you don’t have the cash on hand to cover the taxes owed on the conversion, you may have to dip into your retirement funds. This will erode your nest egg. The more money you convert and the higher your tax bracket, the bigger the tax hit.

Your retirement plans. Your stage of life may also affect your decision. Typically, you wouldn’t convert a traditional IRA to a Roth IRA if you expect to retire soon and start drawing down on the account right away. Usually, the goal is to allow the funds to grow and compound over time without any tax erosion.

Keep in mind that converting a traditional IRA to a Roth isn’t an all-or-nothing deal. You can convert as much or as little of the money from your traditional IRA account as you like. So, you might decide to gradually convert your account to spread out the tax hit over several years.

There are also other issues that need to be considered before executing a Roth IRA conversion. If this sounds like something you’re interested in, contact us to discuss whether a conversion is right for you.

© 2022

Disclosure of contingent liabilities — such as those associated with pending litigation or government investigations — is a gray area in financial reporting. It’s important to keep investors and lenders informed of risks that may affect a company’s future performance. But companies also want to avoid alarming stakeholders with losses that are unlikely to occur or disclosing their litigation strategies.

Understanding the GAAP requirements

Under Accounting Standards Codification (ASC) Topic 450, Contingencies, a company is required to classify contingent losses under the following categories:

Remote. If a contingent loss is remote, the chances that a loss will occur are slight. No disclosure or accrual is usually required for remote contingencies.

Probable. If a contingent loss is probable, it’s likely to occur and the company must record an accrual on the balance sheet and a loss on the income statement if the amount (or a range of amounts) can be reasonably estimated. Otherwise, the company should disclose the nature of the contingency and explain why the amount can’t be estimated. In general, there should be enough disclosure about a probable contingency so the disclosure’s reader can understand its magnitude.

Reasonably possible. If a contingent loss is reasonably possible, it falls somewhere between remote and probable. Here, the company must disclose it but doesn’t need to record an accrual. The disclosure should include an estimate of the amount (or the range of amounts) of the contingent loss or an explanation of why it can’t be estimated.

Making judgment calls

Determining the appropriate classification for a contingent loss requires judgment. It’s important to consider all scenarios and document your analysis of the classification.

In today’s volatile marketplace, conditions can unexpectedly change. You should re-evaluate contingencies each reporting period to determine whether your previous classification remains appropriate. For example, a remote contingent loss may become probable during the reporting period — or you might have additional information about a reasonably possible or probable contingent loss to be able to report an accrual (or update a previous estimate).

Outside expertise

Ultimately, management decides how to classify contingent liabilities. But external auditors will assess the company’s existing classifications and accruals to determine whether they seem appropriate. They’ll also look out for new contingencies that aren’t yet recorded. During fieldwork, your auditors may ask for supporting documentation and recommend adjustments to estimates and disclosures, if necessary, based on current market conditions. Contact us for more information.

© 2022

You can’t stop it; you can only hope to use it to your best business advantage. That’s right, summer is on the way and, with it, a variety of seasonal marketing opportunities for small to midsize companies. Here are three ideas to consider.

1. Support summer camps and local sports

Soon, millions of young people will be attending summer camps, both the “day” and “overnight” variety. Do some research into local options and see whether your business can arrange a sponsorship. If the cost is reasonable, you can get your name and logo on camp t-shirts and other items, where both campers and their parents will see them nearly every day for weeks.

Look into using the same strategy with summer sports. Baseball teams sponsored by local businesses are a time-honored tradition that can still pay off. There might be other, similar options as well.

2. Attend outdoor festivals or other public events

The warmer months mean parades, carnivals, outdoor musical performances and other spectacles of summertime bliss. Investigate the costs and logistics of setting up a booth with clear, attention-grabbing signage. Give out product samples or brochures to inform attendees about your company. You might also hand out small souvenirs, such as key chains, pens or magnets with your contact info.

And don’t just stay in the booth — dispatch employees into the crowd. Have staff members walk around outdoor events with samples or brochures. Just be sure to train them to be friendly and nonconfrontational. If appropriate, employees might wear distinctive clothing or even costumes or sandwich boards to draw attention.

3. Heat up your social media strategy

You probably knew this one was coming! For many, if not most, businesses today, using some form of social media to get the word out and interact with customers is a necessity. But hammering the same message 365 days a year isn’t likely to pay off. Tailor your social media strategy to celebrate summer and inspire interaction.

For example, launch a summertime travel photo contest. Come up with a catchy hashtag, preferably involving your company name, and invite followers to share pics from their summer vacation spots. Offer a nominal prize or enticing discount for the top three entries.

Alternatively, look around for some charitable events or activities that you, your leadership team and employees could participate in this summer. Post a narrative and pictures on your social media channels.

Make the most of midyear

As people head outside and on summer trips, raising awareness of your brand could mean a bump in sales and strong midyear revenues. We can help you assess the costs of potential marketing strategies and measure the return on investment of any you pursue.

© 2022

Many people own Series E and Series EE bonds that were bought many years ago. They may rarely look at them or think about them except on occasional trips to a file cabinet or safe deposit box.

One of the main reasons for buying U.S. savings bonds (such as Series EE bonds) is the fact that interest can build up without the need to currently report or pay tax on it. The accrued interest is added to the redemption value of the bond and is paid when the bond is eventually cashed in. Unfortunately, the law doesn’t allow for this tax-free buildup to continue indefinitely. The difference between the bond’s purchase price and its redemption value is taxable interest.

Series EE bonds, which have a maturity period of 30 years, were first offered in January 1980. They replaced the earlier Series E bonds.

Currently, Series EE bonds are only issued electronically. They’re issued at face value, and the face value plus accrued interest is payable at maturity.

Before January 1, 2012, Series EE bonds could be purchased on paper. Those paper bonds were issued at a discount, and their face value is payable at maturity. Owners of paper Series EE bonds can convert them to electronic bonds, posted at their purchase price (with accrued interest).

Here’s an example of how Series EE bonds are taxed. Bonds issued in January 1990 reached final maturity after 30 years, in January of 2020. That means that not only have they stopped earning interest, but all of the accrued and as yet untaxed interest was taxable in 2020.

A $1,000 Series EE bond (paper) bought in January 1990 for $500 was worth about $2,073.60 in January of 2020. It won’t increase in value after that. The entire difference of $1,573.60 ($2,073.60 − $500) was taxable as interest in 2020. This interest is exempt from state and local income taxes.

Note: Using the money from EE bonds for higher education may keep you from paying federal income tax on the interest.

If you own bonds (paper or electronic) that are reaching final maturity this year, action is needed to assure that there’s no loss of interest or unanticipated current tax consequences. Check the issue dates on your bonds. One possible place to reinvest the money is in Series I savings bonds, which are currently attractive due to rising inflation resulting in a higher interest rate.

© 2022

Are you a partner in a business? You may have come across a situation that’s puzzling. In a given year, you may be taxed on more partnership income than was distributed to you from the partnership in which you’re a partner.

Why does this happen? It’s due to the way partnerships and partners are taxed. Unlike C corporations, partnerships aren’t subject to income tax. Instead, each partner is taxed on the partnership’s earnings — whether or not they’re distributed. Similarly, if a partnership has a loss, the loss is passed through to the partners. (However, various rules may prevent a partner from currently using his or her share of a partnership’s loss to offset other income.)

Pass through your share

While a partnership isn’t subject to income tax, it’s treated as a separate entity for purposes of determining its income, gains, losses, deductions and credits. This makes it possible to pass through to partners their share of these items.

An information return must be filed by a partnership. On Schedule K of Form 1065, the partnership separately identifies income, deductions, credits and other items. This is so that each partner can properly treat items that are subject to limits or other rules that could affect their correct treatment at the partner’s level. Examples of such items include capital gains and losses, interest expense on investment debts and charitable contributions. Each partner gets a Schedule K-1 showing his or her share of partnership items.

Basis and distribution rules ensure that partners aren’t taxed twice. A partner’s initial basis in his or her partnership interest (the determination of which varies depending on how the interest was acquired) is increased by his or her share of partnership taxable income. When that income is paid out to partners in cash, they aren’t taxed on the cash if they have sufficient basis. Instead, partners just reduce their basis by the amount of the distribution. If a cash distribution exceeds a partner’s basis, then the excess is taxed to the partner as a gain, which often is a capital gain.

Illustrative example

Two people each contribute $10,000 to form a partnership. The partnership has $80,000 of taxable income in the first year, during which it makes no cash distributions to the two partners. Each of them reports $40,000 of taxable income from the partnership as shown on their K-1s. Each has a starting basis of $10,000, which is increased by $40,000 to $50,000. In the second year, the partnership breaks even (has zero taxable income) and distributes $40,000 to each of the two partners. The cash distributed to them is received tax-free. Each of them, however, must reduce the basis in his or her partnership interest from $50,000 to $10,000.

More rules and limits

The example and details above are an overview and, therefore, don’t cover all the rules. For example, many other events require basis adjustments and there are a host of special rules covering noncash distributions, distributions of securities, liquidating distributions and other matters. Contact us if you’d like to discuss how a partner is taxed.

© 2022

Back in late 2019, the first significant legislation addressing retirement savings since 2006 became law. The Setting Every Community Up for Retirement Enhancement (SECURE) Act has resulted in many changes to retirement and estate planning strategies, but it also raised some questions. The IRS has been left to fill the gaps, most recently with the February 2022 release of proposed regulations that have left many taxpayers confused and unsure of how to proceed.

The proposed regs cover numerous topics, but one of the most noteworthy is an unexpected interpretation of the so-called “10-year rule” for inherited IRAs and other defined contribution plans. If finalized, this interpretation — which contradicts earlier IRS guidance — could lead to larger tax bills for certain beneficiaries.

Birth of the 10-year rule

Before the SECURE Act was enacted, beneficiaries of inherited IRAs could “stretch” the required minimum distributions (RMDs) on such accounts over their entire life expectancies. The stretch period could be decades for younger heirs, meaning they could take smaller distributions and defer taxes while the accounts grew.

In an effort to accelerate tax collection, the SECURE Act eliminated the rules that allowed stretch IRAs for many heirs. For IRA owners or defined contribution plan participants who die in 2020 or later, the law generally requires that the entire balance of the account be distributed within 10 years of death. This rule applies regardless of whether the deceased died before, on or after the required beginning date (RBD) for RMDs. Under the SECURE Act, the RBD is age 72.

The SECURE Act recognizes exceptions for the following types of “eligible designated beneficiaries” (EDBs):

- Surviving spouses,

- Children younger than “the age of majority,”

- Individuals with disabilities,

- Chronically ill individuals, and

- Individuals who are no more than 10 years younger than the account owner.

EDBs may continue to stretch payments over their life expectancies (or, if the deceased died before the RBD, they may elect the 10-year rule treatment). The 10-year rule will apply to the remaining amounts when an EDB dies.

The 10-year rule also applies to trusts, including see-through or conduit trusts that use the age of the oldest beneficiary to stretch RMDs and prevent young or spendthrift beneficiaries from rapidly draining inherited accounts.

Prior to the release of the proposed regs, the expectation was that non-EDBs could wait until the end of the 10-year period and take the entire account as a lump-sum distribution, rather than taking annual taxable RMDs. This distribution approach generally would be preferable, especially if an heir is working during the 10 years and in a higher tax bracket. Such heirs could end up on the hook for greater taxes than anticipated if they must take annual RMDs.

The IRS has now muddied the waters with conflicting guidance. In March 2021, it published an updated Publication 590-B, “Distributions from Individual Retirement Arrangements (IRAs),” which suggested that annual RMDs would indeed be required for years one through nine post-death. But, just a few months later, it again revised the publication to specify that “the beneficiary is allowed, but not required, to take distributions prior to” the 10-year deadline.

That position didn’t last long. The proposed regs issued in February call for annual RMDs in certain circumstances.

Proposed regs regarding the 10-year rule

According to the proposed regs, as of January 1, 2022, non-EDBs who inherit an IRA or defined contribution plan before the deceased’s RBD satisfy the 10-year rule simply by taking the entire sum before the end of the calendar year that includes the 10th anniversary of the death. The regs take a different tack when the deceased passed on or after the RBD.

In that case, non-EDBs must take annual RMDs (based on their life expectancies) in year one through nine, receiving the remaining balance in year 10. The annual RMD rule gives beneficiaries less flexibility and could push them into higher tax brackets during those years. (Note that Roth IRAs don’t have RMDs, so beneficiaries need only empty the accounts by the end of 10 years.)

Aside from those tax implications, this stance creates a conundrum for non-EDBs who inherited an IRA or defined contribution plan in 2020. Under the proposed regs, they should have taken an annual RMD for 2021, seemingly subjecting them to a penalty for failure to do so, equal to 50% of the RMD they were required to take. But the proposed regs didn’t come out until February of 2022.

What about non-EDBs who are minors when they inherit the account but reach the “age of majority” during the 10-year post-death period? Those beneficiaries can use the stretch rule while minors, but the annual RMD will apply after the age of majority (assuming the deceased died on or after the RBD).

If the IRS’s most recent interpretation of the 10-year rule sticks, non-EDBs will need to engage in tax planning much sooner than they otherwise would. For example, it could be wise to take more than the annual RMD amount to more evenly spread out the tax burden over the 10 years. They also might want to adjust annual distribution amounts based on factors such as other income or deductions for a particular tax year.

Clarifications of the exceptions

The proposed regs clarify some of the terms relevant to determining whether an heir is an EDB. For example, they define the “age of majority” as age 21 — regardless of how the term is defined under the applicable state law.

The definition of “disability” turns on the beneficiary’s age. If under age 18 at the time of the deceased’s death, the beneficiary must have a medically determinable physical or mental impairment that 1) results in marked and severe functional limitations, and 2) can be expected to result in death or be of long-continued and indefinite duration. Beneficiaries age 18 or older are evaluated under a provision of the tax code that considers whether the individual is “unable to engage in substantial gainful activity.”

Wait and see?

The U.S. Treasury Department is accepting comments on the proposed regs through May 25, 2022, and will hold a public hearing on June 15, 2022. Non-EDBs who missed 2021 RMDs may want to delay action to see if more definitive guidance comes out before year-end, including, ideally, relief for those who relied on the version of Publication 590-B that indicated RMDs weren’t necessary. As always, though, contact us to determine the best course for you in light of new developments.

© 2022

What Governments Need to Know Now for GASB 87 – Leases

URGENT! Your budget may NEED TO BE AMENDED to coincide with the implementation of GASB 87.

Background

Ready or not…GASB Statement No. 87 – Leases is here! This GASB must be implemented in the June 30, 2022 financial statements. GASB 87 requires a lessee to recognize a lease liability and an intangible right-to-use lease asset, and a lessor is required to recognize a lease receivable and a deferred inflow of resources.

Practical hint: Short-term (less than one year) leases will be recorded as operating leases had been.

What to do now

Get lease information ready, amend the fiscal year 2021-22 budget for any new current year leases (exceeding one year), and make journal entries for leases before closing out the current fiscal year.

Information to collect

For current leases:

- Lease description

- Original lease term

- Any renewal options, and the determination of the likelihood of utilizing those options

- Components of the payments (fixed, variable, interest rate)

- Who has the right to terminate the lease

- Lease obligation maturities for the next five years and beyond (similar to debt maturity schedule)

Leases initiated after 7/1/21 (in this fiscal year):

- Calculate the right-of-use asset and lease liability. Practical hint: Total cost of leased equipment (as if a “capital lease”).

- Governmental Fund Level: In the current fiscal year ending June 30, 2022 – this will be included as a:

- Revenue: Other financing sources – lease financing

- Expenditure: Lease right-to-use assets (capital outlay)

- URGENT: Include Revenue and Expenditure amounts in final budget amendments for the current fiscal year for the Governmental Funds (ending June 30, 2022).

- Business-type funds, Internal Service Funds, and Government-wide level: In the current fiscal year ending June 30, 2022 – this will be included as:

- Asset: Right-to-use assets

- Liability: Lease liability

Your Yeo & Yeo professionals will provide additional guidance and individual assistance during the audit process.

Background

It is here – GASB Statement No. 87, Leases. This GASB must be implemented in school districts’ June 30, 2022, financial statements. The objective of the new GASB is to improve accounting and financial reporting for leases. Another objective is to increase financial statements’ usefulness by recognizing certain lease assets and liabilities for leases that were previously classified as operating leases and recognized as inflows or outflows of resources based on the contract’s payment provisions. GASB 87 requires a lessee to recognize a lease liability and an intangible right-to-use lease asset. A lessor must recognize a lease receivable and a deferred inflow of resources.

What to do now

Get lease information ready, amend the fiscal year 2021-22 budget for any new current year leases (exceeding one year), and make journal entries for leases before closing out the current fiscal year.

Information to collect

For current leases:

- Lease description

- Original lease term

- Any renewal options, and the determination of the likelihood of utilizing those options

- Components of the payments (fixed, variable, interest rate)

- Who has the right to terminate the lease

- Lease obligation maturities for the next five years and beyond (similar to debt maturity schedule)

Practical hint: Short-term (less than one year) leases will be recorded as operating leases had been. Leases over one year will be recorded on district-wide financials, and in the year of inception, the lease will be recorded on the fund level statements.

How to Calculate

Leases (where the district is the lessee) existing prior to 7/1/21 (before this fiscal year)

- Calculate lease liability as of 7/1/21. This will be the right-of-use asset and liability for district-wide beginning balances.

- This will not change fund level statements.

Leases existing after 7/1/21 (in this fiscal year)

- Calculate the right-of-use asset/lease liability. Practical hint: Total cost of leased equipment (as if a “capital lease”).

- Fund level: In the current fiscal year ending June 30, 2022 – this will be included as a:

- Revenue: Other financing sources – lease financing

- Expenditure: Lease right-to-use assets (capital outlay)

- URGENT: Include Revenue and Expenditure amounts in final budget amendments for the current fiscal year (ending June 30, 2022).

- District-wide level: In the current fiscal year ending June 30, 2022 – this will be included as:

- Asset: Right-to-use assets

- Liability: Lease liability

Leases (where the district is the lessor)

- Calculate lease receivable as of 6/30/2022. This will be recorded as an Account Receivable and Deferred inflow.

- This will change fund level statements. It will be on both the district-wide and governmental fund statements.

For the fiscal year 2022-23 and beyond, maintain the above list of information on leases. Work with your auditor, if necessary, to determine which leases require the underlying asset to be recorded as a right-to-use asset and include such leases in budgets going forward.

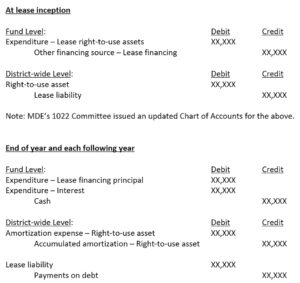

Journal Entries

Are you a charitably minded individual who is also taking distributions from a traditional IRA? You may want to consider the tax advantages of making a cash donation to an IRS-approved charity out of your IRA.

When distributions are taken directly out of traditional IRAs, federal income tax of up to 37% in 2022 will have to be paid. State income taxes may also be owed.

Qualified charitable distributions

One popular way to transfer IRA assets to charity is via a tax provision that allows IRA owners who are age 70½ or older to direct up to $100,000 per year of their IRA distributions to charity. These distributions are known as qualified charitable distributions (QCDs). The money given to charity counts toward your required minimum distributions (RMDs) but doesn’t increase your adjusted gross income (AGI) or generate a tax bill.

Keeping the donation out of your AGI may be important for several reasons. Here are some of them:

- It can help you qualify for other tax breaks. For example, having a lower AGI can reduce the threshold for deducting medical expenses, which are only deductible to the extent they exceed 7.5% of AGI.

- You can avoid rules that can cause some or all of your Social Security benefits to be taxed and some or all of your investment income to be hit with the 3.8% net investment income tax.

- It can help you avoid a high-income surcharge for Medicare Part B and Part D premiums, which kick in if AGI is over certain levels.

- The distributions going to the charity won’t be subject to federal estate tax and generally won’t be subject to state death taxes.

Important points: You can’t claim a charitable contribution deduction for a QCD not included in your income. Also keep in mind that the age after which you must begin taking RMDs is 72, but the age you can begin making QCDs is 70½.

To benefit from a QCD for 2022, you must arrange for a distribution to be paid directly from the IRA to a qualified charity by December 31, 2022. You can use QCDs to satisfy all or part of the amount of your RMDs from your IRA. For example, if your 2022 RMDs are $10,000, and you make a $5,000 QCD for 2022, you have to withdraw another $5,000 to satisfy your 2022 RMDs.

Other rules and limits may apply. Want more information? Contact us to see whether this strategy would be beneficial in your situation.

© 2022

Businesses should be aware that they may be responsible for issuing more information reporting forms for 2022 because more workers may fall into the required range of income to be reported. Beginning this year, the threshold has dropped significantly for the filing of Form 1099-K, “Payment Card and Third-Party Network Transactions.” Businesses and workers in certain industries may receive more of these forms and some people may even get them based on personal transactions.

Background of the change

Banks and online payment networks — payment settlement entities (PSEs) or third-party settlement organizations (TPSOs) — must report payments in a trade or business to the IRS and recipients. This is done on Form 1099-K. These entities include Venmo and CashApp, as well as gig economy facilitators such as Uber and TaskRabbit.

A 2021 law dropped the minimum threshold for PSEs to file Form 1099-K for a taxpayer from $20,000 of reportable payments made to the taxpayer and 200 transactions to $600 (the same threshold applicable to other Forms 1099) starting in 2022. The lower threshold for filing 1099-K forms means many participants in the gig economy will be getting the forms for the first time.

Members of Congress have introduced bills to raise the threshold back to $20,000 and 200 transactions, but there’s no guarantee that they’ll pass. In addition, taxpayers should generally be reporting income from their side employment engagements, whether it’s reported to the IRS or not. For example, freelancers who make money creating products for an Etsy business or driving for Uber should have been paying taxes all along. However, Congress and the IRS have said this responsibility is often ignored. In some cases, taxpayers may not even be aware that income from these sources is taxable.

Some taxpayers may first notice this change when they receive their Forms 1099-K in January 2023. However, businesses should be preparing during 2022 to minimize the tax consequences of the gross amount of Form 1099-K reportable payments.

What to do now

Taxpayers should be reviewing gig and other reportable activities. Make sure payments are being recorded accurately. Payments received in a trade or business should be reported in full so that workers can withhold and pay taxes accordingly.

If you receive income from certain activities, you may want to increase your tax withholding or, if necessary, make estimated tax payments or larger payments to avoid penalties.

Separate personal payments and track deductions

Taxpayers should separate taxable gross receipts received through a PSE that are income from personal expenses, such as splitting the check at a restaurant or giving a gift. PSEs can’t necessarily distinguish between personal expenses and business payments, so taxpayers should maintain separate accounts for each type of payment.

Keep in mind that taxpayers who haven’t been reporting all income from gig work may not have been documenting all deductions. They should start doing so now to minimize the taxable income recognized due to the gross receipts reported on Form 1099-K. The IRS is likely to take the position that all of a taxpayer’s gross receipts reported on Form 1099-K are income and won’t allow deductions unless the taxpayer substantiates them. Deductions will vary based on the nature of the taxpayer’s work.

Contact us if you have questions about your Form 1099-K responsibilities.

© 2022

When creating forward-looking financials, you generally have two options under AICPA Attestation Standards Section 301, Financial Forecasts and Projections:

1. Forecast. Prospective financial statements that present, to the best of the responsible party’s knowledge and belief, an entity’s expected financial position, results of operations and cash flows. A financial forecast is based on the responsible party’s assumptions reflecting the conditions it expects to exist and the course of action it expects to take.

2. Projection. Prospective financial statements that present, to the best of the responsible party’s knowledge and belief, given one or more hypothetical assumptions, an entity’s expected financial position, results of operations and cash flows. A financial projection is sometimes prepared to present one or more hypothetical courses of action for evaluation, as in response to a question such as, “What would happen if … ?”

Subtle difference

The terms “forecast” and “projection” are sometimes used interchangeably. But there’s a noteworthy distinction, a forecast represents expected results based on the expected course of action. These are the most common type of prospective reports for companies with steady historical performance that plan to maintain the status quo.

On the flip side, a projection estimates the company’s expected results based on various hypothetical situations that may or may not occur. These statements are typically used when management is uncertain whether performance targets will be met. So, they may be appropriate for start-ups or when evaluating results over a longer period because there’s a good chance that customer demand or market conditions could change over time.

Critical components

Regardless of whether you opt for a forecast or projection, the report will generally be organized using the same format as your financial statements with an income statement, balance sheet and cash flow statement. Most prospective statements conclude with a statement of key assumptions that underlie the numbers. Many assumptions are driven by your company’s historical financial statements, along with a detailed sales budget for the year.

Instead of relying on static forecasts or projections — which can quickly become outdated in a volatile marketplace — some companies now use rolling 12-month versions that are adaptable and look beyond year end. This helps you identify and respond to weaknesses in your assumptions, as well as unexpected changes in the marketplace. For example, a manufacturer that experiences a shortage of raw materials could experience an unexpected drop in sales until conditions improve. If the company maintains a rolling forecast, it would be able to revise its plans for such a temporary disruption.

Contact us

Planning for the future is an important part of running a successful business. While no forecast or projection will be 100% accurate in these uncertain times, we can help you evaluate the alternatives for issuing prospective financial statements and offer fresh, objective insights about what may lie ahead for your business.

© 2022

Taking care of an elderly parent or grandparent may provide more than just personal satisfaction. You could also be eligible for tax breaks. Here’s a rundown of some of them.

1. Medical expenses. If the individual qualifies as your “medical dependent,” and you itemize deductions on your tax return, you can include any medical expenses you incur for the individual along with your own when determining your medical deduction. The test for determining whether an individual qualifies as your “medical dependent” is less stringent than that used to determine whether an individual is your “dependent,” which is discussed below. In general, an individual qualifies as a medical dependent if you provide over 50% of his or her support, including medical costs.

However, bear in mind that medical expenses are deductible only to the extent they exceed 7.5% of your adjusted gross income (AGI).

The costs of qualified long-term care services required by a chronically ill individual and eligible long-term care insurance premiums are included in the definition of deductible medical expenses. There’s an annual cap on the amount of premiums that can be deducted. The cap is based on age, going as high as $5,640 for 2022 for an individual over 70.

2. Filing status. If you aren’t married, you may qualify for “head of household” status by virtue of the individual you’re caring for. You can claim this status if:

- The person you’re caring for lives in your household,

- You cover more than half the household costs,

- The person qualifies as your “dependent,” and

- The person is a relative.

If the person you’re caring for is your parent, the person doesn’t need to live with you, so long as you provide more than half of the person’s household costs and the person qualifies as your dependent. A head of household has a higher standard deduction and lower tax rates than a single filer.

3. Tests for determining whether your loved one is a “dependent.” Dependency exemptions are suspended (or disallowed) for 2018–2025. Even though the dependency exemption is currently suspended, the dependencytests still apply when it comes to determining whether a taxpayer is entitled to various other tax benefits, such as head-of-household filing status.

For an individual to qualify as your “dependent,” the following must be true for the tax year at issue:

- You must provide more than 50% of the individual’s support costs,

- The individual must either live with you or be related,

- The individual must not have gross income in excess of an inflation-adjusted exemption amount,

- The individual can’t file a joint return for the year, and

- The individual must be a U.S. citizen or a resident of the U.S., Canada or Mexico.

4. Dependent care credit. If the cared-for individual qualifies as your dependent, lives with you, and physically or mentally can’t take care of him- or herself, you may qualify for the dependent care credit for costs you incur for the individual’s care to enable you and your spouse to go to work.

Contact us if you’d like to further discuss the tax aspects of financially supporting and caring for an elderly relative.

© 2022

At Yeo & Yeo CPAs & Business Consultants, we take pride in creating an environment that challenges, supports and rewards our employees. We are family-focused, community-driven and relationship-oriented. And we love to see our employees grow and succeed.

We are honored to have been named one of West Michigan’s Best and Brightest Companies to Work For for the eighteenth consecutive year. The Best and Brightest programs identify, recognize and celebrate organizations that exemplify Better Business. Richer Lives. Stronger Communities.

Yeo & Yeo is proud of the environment we have created for our employees. We offer an award-winning CPA certification bonus program, gold standard benefits, and hybrid and remote work capabilities. Our West Michigan staff shared five reasons why our firm is such a great place to work:

- Empowerment: “In my second year as a partner, I was allowed to lead the firm’s Tax Service Line. I am grateful for the trust the firm’s leadership placed in me, especially as a younger professional at the time. As a firm, we empower our employees to lead and give them opportunities for growth and development throughout their careers.” – David Jewell, CPA, Managing Principal

- Flexibility: “One of the things I appreciate about Yeo & Yeo is that the company recognizes that each employee is different, and is willing to be flexible to accommodate each employee’s needs. We don’t have a set work schedule that everyone has to adhere to, and we are encouraged to find a path within the company that works for us and what we want to accomplish.” – Megan Taylor, CPA, Manager

- Family-focused: “I appreciate that we’re given the respect and autonomy to have flexible work schedules. We’re trusted to complete the work and given opportunities to enjoy a rewarding career without compromising on personal, family time.” – Chelsea Meyer, CPA, Manager

- Relationships: “We are not a big four firm. Everyone is not just a number. We really help each other on an individual level. We feel like we are a family. It doesn’t matter where you sit. We all work together.” – Michael Oliphant, CPA, CVA, Principal

- People first: “Yeo & Yeo treats you well. As a first-year principal, I can wholeheartedly say that the decisions the partner group makes are always in the best interest of the employees. They listen and respond. They work hard every day to create an inclusive and supportive environment. I am lucky to be around such a great group of professionals.” – Michael Evrard, CPA, Principal

What will your story be? Apply today to write the next chapter in your career.

The IRS recently released guidance providing the 2023 inflation-adjusted amounts for Health Savings Accounts (HSAs). High inflation rates will result in next year’s amounts being increased more than they have been in recent years.

HSA basics

An HSA is a trust created or organized exclusively for the purpose of paying the “qualified medical expenses” of an “account beneficiary.” An HSA can only be established for the benefit of an “eligible individual” who is covered under a “high deductible health plan.” In addition, a participant can’t be enrolled in Medicare or have other health coverage (exceptions include dental, vision, long-term care, accident and specific disease insurance).

A high deductible health plan (HDHP) is generally a plan with an annual deductible that isn’t less than $1,000 for self-only coverage and $2,000 for family coverage. In addition, the sum of the annual deductible and other annual out-of-pocket expenses required to be paid under the plan for covered benefits (but not for premiums) can’t exceed $5,000 for self-only coverage, and $10,000 for family coverage.

Within specified dollar limits, an above-the-line tax deduction is allowed for an individual’s contribution to an HSA. This annual contribution limitation and the annual deductible and out-of-pocket expenses under the tax code are adjusted annually for inflation.

Inflation adjustments for next year

In Revenue Procedure 2022-24, the IRS released the 2023 inflation-adjusted figures for contributions to HSAs, which are as follows:

Annual contribution limitation. For calendar year 2023, the annual contribution limitation for an individual with self-only coverage under an HDHP will be $3,850. For an individual with family coverage, the amount will be $7,750. This is up from $3,650 and $7,300, respectively, for 2022.

In addition, for both 2022 and 2023, there’s a $1,000 catch-up contribution amount for those who are age 55 and older at the end of the tax year.

High deductible health plan defined. For calendar year 2023, an HDHP will be a health plan with an annual deductible that isn’t less than $1,500 for self-only coverage or $3,000 for family coverage (these amounts are $1,400 and $2,800 for 2022). In addition, annual out-of-pocket expenses (deductibles, co-payments, and other amounts, but not premiums) won’t be able to exceed $7,500 for self-only coverage or $15,000 for family coverage (up from $7,050 and $14,100, respectively, for 2022).

Reap the rewards

There are a variety of benefits to HSAs. Contributions to the accounts are made on a pre-tax basis. The money can accumulate tax free year after year and can be withdrawn tax free to pay for a variety of medical expenses such as doctor visits, prescriptions, chiropractic care and premiums for long-term care insurance. In addition, an HSA is “portable.” It stays with an account holder if he or she changes employers or leaves the workforce. If you have questions about HSAs at your business, contact your employee benefits and tax advisors.

© 2022